Creativity, the ability to make or otherwise bring into existence something new, whether a new solution to a problem, a new method or device, or a new artistic object or form. www.brittanica.com

Creative communication engages, occupies and pays the salaries of many in our industry. But does creativity really create value? Let’s dig a little into the issue ..

The problem

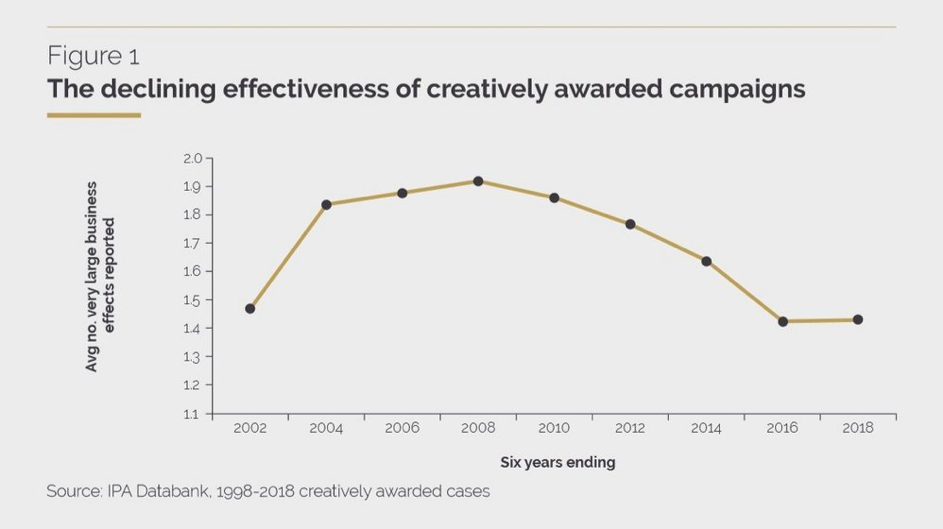

Is the effectiveness of creativity declining or even disappearing? It has been discussed for a some time, and increasingly so after a new study from Peter Field, ”The Crisis in Creative Effectiveness” was released.

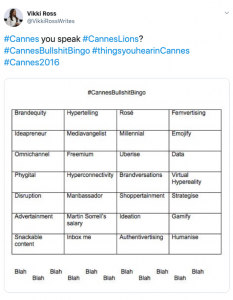

The research compares data on marketing performance (PIA Effectiveness Awards: share of the market, brand equity, profitability etc.) with data on success in advertising from WARC Rankings (Cannes Lions, Clio, D&AD etc). The study covers 600 cases between 1996 to 2018 and the result is bleak to say the least. A prize winning campaign in 2018 is less effective than ever during the 24 years that the study covers, and it has no advantage compared to a non-prize winning campaign. In other words: Usually a Cannes Lion meant that the awarded company would gain success but that correlation can no longer be established.

Is this true?

In my humble opinion, there are a few questions you could raise. Marketing Guru Mark Ritson has touched upon this as well, mainly on these grounds;

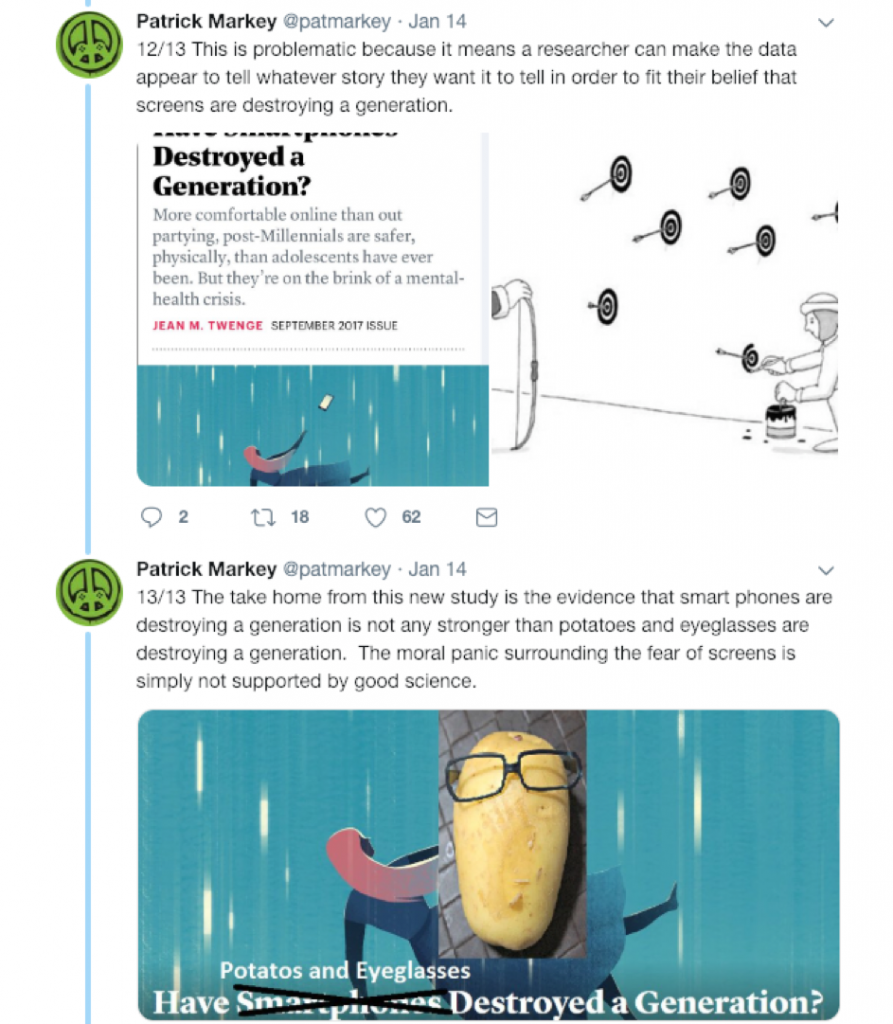

Correlation vs causality? The study compares two sets of data (success on the market and number of creative awards) and shows a that the connection between the two have become weaker. However, that doesn’t necessarily mean that there is a causality between the two. Does prize winning campaigns give commercial success or is it companies that are in a “flow” of commercial success that can afford prize winning advertising? Or, are there other external factors (distribution/legislation/state of the market) behind the success?

Selection The campaigns that enters IPA Effectiveness Awards and major creativity awards has been through a selection. It costs both time and money to enter awards and some companies do not participate for reasons of principle. So are the campaigns that enter advertising awards representative for the market in general? Some people consider (Rory Sutherland for example) that advertising awards is an arena for advertising agencies showing off to the advertising industry, rather than an award show for effectiveness)

On an overall level (and also confessing I don’t know enough about the methodology) I would say that Peter Fields study has empiricism and that the trend in it is so pronounced it cannot be denied. I also feel that there are small indications on other data points that supports the theory. For instance, the TGI survey carried out in Britain where consumers were asked whether the find advertising on television as entertaining as the actual TV shows;

The reason behind all this?

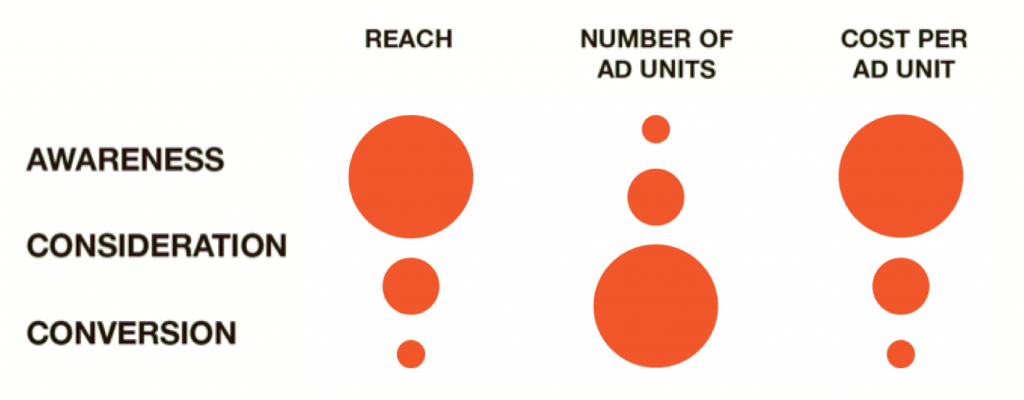

There are of course a number of things causing this, but most originate from the conflict between short term vs long term. This discussion in turn originates from the Binet & Field study “The Long and the Short of it”. This study shows that communication based on short term KPIs (sales/awareness/digital engagement) over time is essentially different from communication built on long term KPIs (share of market/price etc.) It has also been known that companies focus too much on campaigns and other efforts with short term goals.

When looking at creative awards, it also appears that an increasing share of awarded campaigns base their submissions on short term results (6 months or less).

What might be the underlying reasons for this short term focus?

The sheer number of short term KIPs Digitisation has increased the amount of short-term KPIs one can look at, while the long-term ones are fairly constant. It is of course easier to base you work on data that is easily available, updated in real-time and often free.

Career acceleration CMO:s are said to change jobs most often than any other members of the C-suite. If you are in a position for three years and want to make your mark it is easier to do so focusing on short term optimisation projects.

Short attention span A personal reflection: In a time where we are expecting faster information, news and updates – are we more reluctant to judge campaigns on whether they are fresh and compelling or not? A consistent, strategic and long-term campaign might feel out of date when it is presented to the jury?

What can be done do about this?

This is basically a two-part answer: First of all, how do we create better advertising that builds real value. And then how do we make sure we reward and highlight good advertising in a better way, in competitions not least.

If we look at the first part there is a lot of interesting literature, from Binet & Field to Byron Sharp and Mark Ritson. (I have tried to gather some interesting thoughts in a brochure available for download here).

Among all these, I think it may be interesting to highlight Jenni Romaniuk, who has done some solid research on how to use brand assets to link separate (short term) campaigns and channels to build synergies and value over time.

There is no shortage of facts and arguments that support a more long-term overall thinking. The difficult thing seems to be to get it implemented in practice. It does, however, feel like we are now in a bit of a trend where these topics are being debated more and more, a discussion which hopefully can create an impact at the CMO level.

When it comes to the relevance of competitions and how we make sure to pay attention to the right things, Peter Field suggests in his study that two separate disciplines should be created in award shows: Prices for short-term efforts and long-term campaigns should be kept apart. It’s an interesting thought. Long term categories may be more planning-driven than creator-driven. More strategy than crafts. More models and figures than execution and wow-factor. One can only hope that we are an industry that has long-term vision and patience to sit through those categories. We might learn a lot.