Taktisk digital performance marketing har levt och frodats i 15-20 år nu, men fenomenet är ändå en ungtupp i relation till reklam överlag. Det är en disciplin som absolut har sina utmaningar, men som trots sin ungdom nått fram till vissa insikter som den mer traditionella reklamen har svårt att konsekvent förhålla sig till.

Den digitala reklamen är bokstavligt talat nedlusad med data, data som inte bara går ner på detaljnivå utan dessutom flödar kontinuerligt över tid. Den digitala reklamen har dessutom mycket lägre trösklar än den traditionella. Det krävs ingen tryckkostnad som för en utomhus-serie, det krävs inget årsavtal i mångmiljonklassen som för TV, det krävs ingen dyr fotoproduktion för en glossig printannons. Dessa faktorer har lett till en ny typ av insikter..

Jag arbetade själv med digitalt på den tiden sök började bli en del av mediemixen. På den tiden hade man kanske en kampanjperiod i breda medier på 4 veckor, sen lite banners i 6 veckor, och köpt sök i 8 veckor. Sen stängde man ner söket för den kampanjen. Det kändes ju lite barockt; Vi kunde köpa in trafik från massor av intresserade människor, vi betalade bara per klick.. och så skulle vi sluta efter 8 veckor. Datan visade ju att det fanns mer intresse att fånga upp på Google?

På samma sätt som det kändes konstigt att inte vara närvarande när det fanns ett intresse att fånga, gick det inte heller att lägga hur mycket pengar som helst på sök. Fanns det inga sökningar kunde man ju inte köpa synlighet på dom. Till skillnad från ”push-reklam” där man kunde bränna enorma summor på att skrika ut sitt budskap.

Dessutom fann man sig i en ny situation där det handlade det om att välja söktermer att köpa. Att man inte kunde bara välja branschtermer att trycka på konsumenter, utan behövde se vad de faktiskt sökte på. CHOCKEN när det då visade sig att folk inte sökte på exakt produktens korrekta namn, varumärkets korrekta stavning, eller fraser från TV-reklamen..

Kort sagt tvingades man till en ödmjukhet inför konsumenters faktiska beteende. Inför hur mycket konsumenter struntar i vad reklam och varumärken försöker få dem att tycka, eller i vilka veckor ett företag vill att man intresserar sig för ett kampanjbudskap, hur de är otrogna mellan varumärken och utgår ifrån sina egna liv, inte en kampanjplan. Man ägnar minimal tankekraft åt reklam, och plockar bara upp de mest basala och simplistiska delar i reklambudskap – om några. Och man ger sig i stort sett uteslutande in i köpprocess när man har ett tydligt behov, inte när det ligger en reklamkampanj. Alltså behövde man finnas tillgänglig kontinuerligt, och ligga live parallellt med alla relevanta erbjudanden man hade mot marknaden,

Vad kan då varumärkesvärlden lära sig? Jag tror man kan se två huvudspår:

Dumb it down / no one cares. När man hela tiden översköljs av data som visar hur konsumenter agerar tvingas man att bli ödmjuk inför konsumenter. I det mer storslagna kampanjarbetet har man mycket mindre och mycket långsammare data. Att få en kampanjmätning kan ta en månad, att se resultat i en brand trackning kan ta ett halvår. Då finns en risk att man redan gott vidare till nästa projekt. Och att man utgår allt för mycket från inifrån ock ut-perspektiv, att man utgår ifrån vad man vill att konsumenter ska tänka och tycka, inte vad man realistiskt har en chans att få in i konsumenters tankevärld. Man hamnar med I detaljerande differentierande budskap, snarare än att bara gå på ryggradsreflexer och distinctiveness. Man utgår för mycket sitt eget språk, och antar att konsumenter har lika mycket förkunskaper om varumärket och dess konkurrenter som man har på marknadsavdelningen. Man pratar eget språk och använder sitt eget lingo, istället för att förenkla.

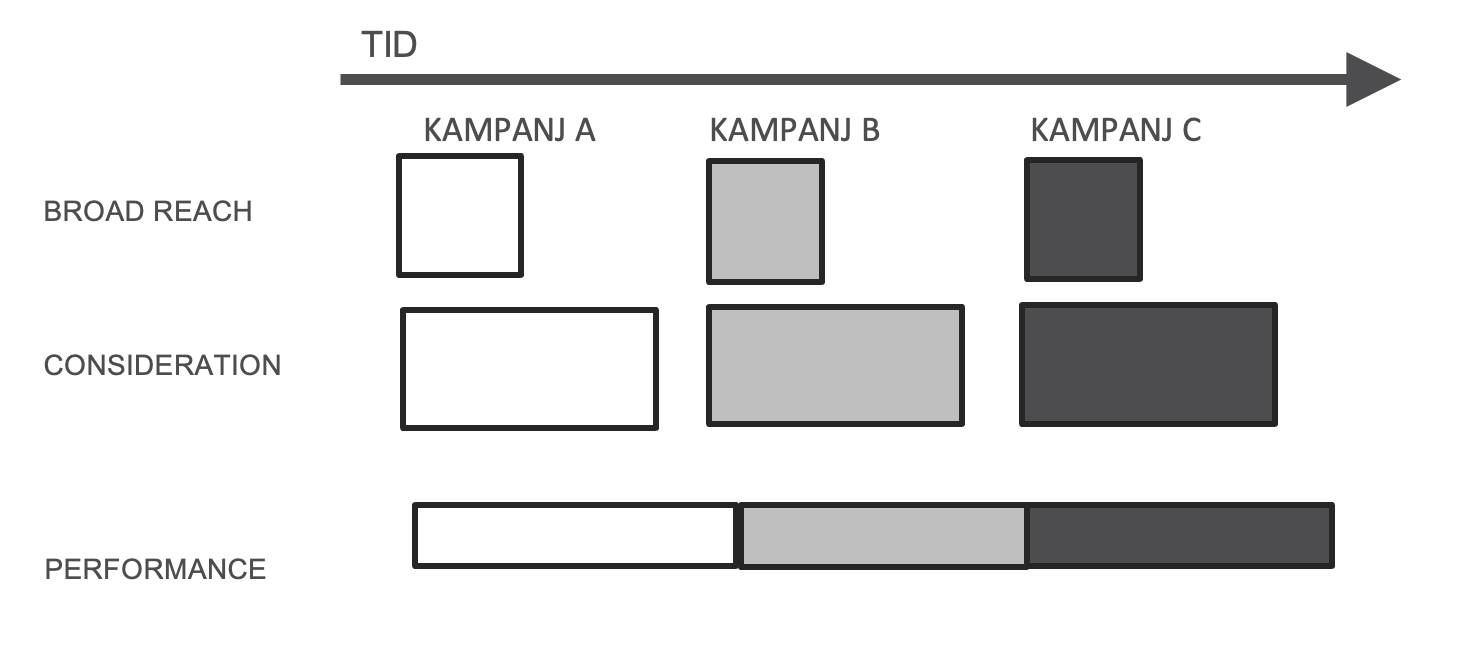

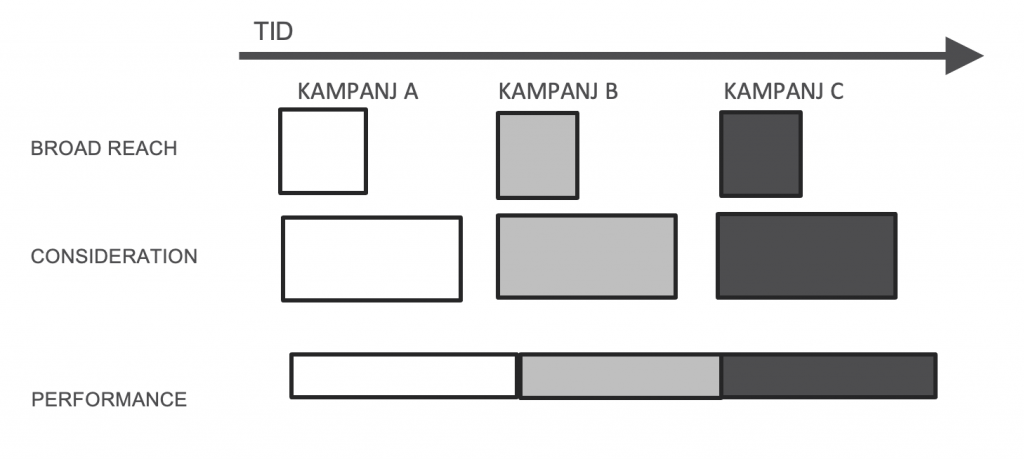

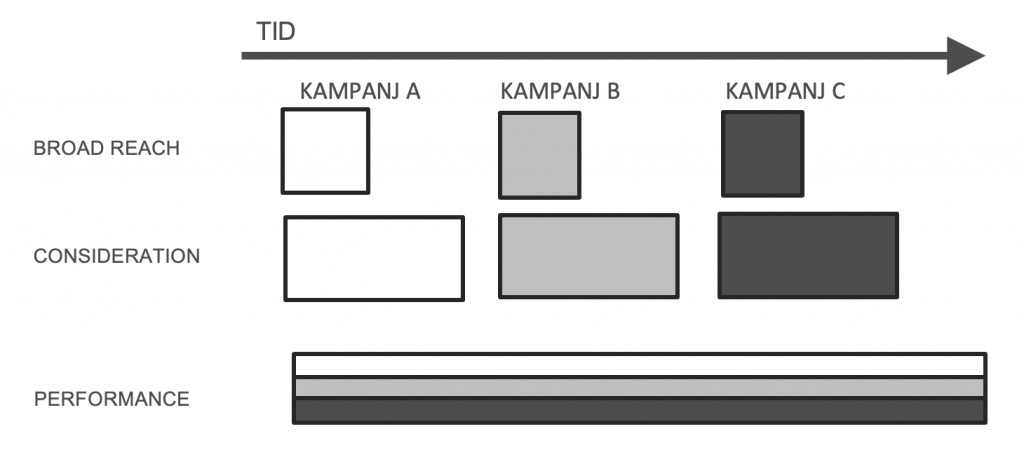

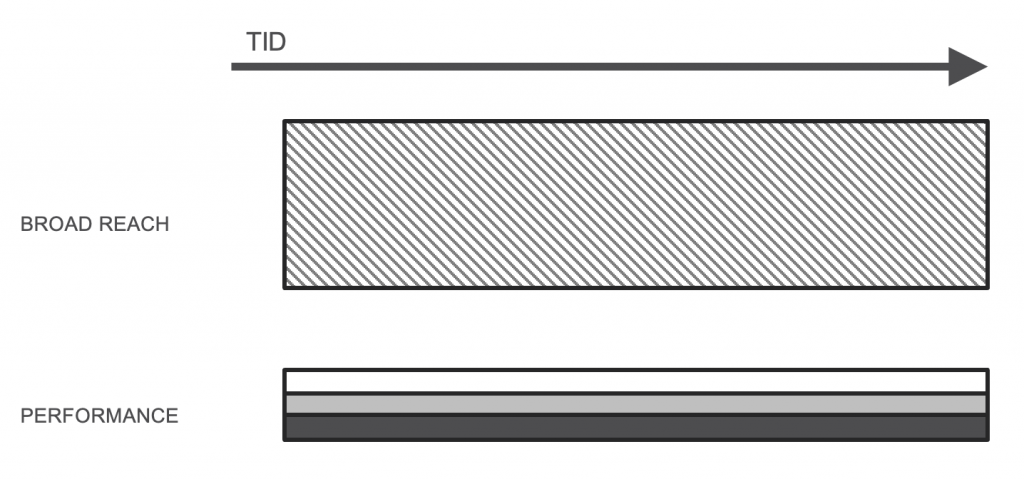

Always on Att ha ett utifrån in-perspektiv innebär också att vara ödmjuk inför att folk påverkas av reklam kontinuerligt. Dels byggs varumärkesassociationer och ”mental avaliability” upp över flera års tid, dels kommer konsumenter (för de flesta produkter) in i aktivt köpbeteende under hela året. Att därför ha en möjlighet att vara närvarande över hela året, alltid finnas tillgänglig, skruva upp och ner volym beroende på behov, är helt enkelt logiskt. Ett always on-tänk har dessutom flera andra fördelar; Genom kontinuerlig närvaro ligger grejer live länge nog för att kunna hinna utvärderas och optimeras innan de byts ut, man får möjlighet att A/B testa saker. Man ser till att alltid ha relevant content att ta ut till marknaden, så man blir inte beroende av kreativ produktion för att snabbt kunna skruva upp volymen i medietryck. Eftersom man är live kontinuerligt tvingas man att tänka kring var som skall vara konstant och gemensamt över tid, och vad som skall uppdateras, vad som är distinctive brand assets och vad som är kampanjspecifikt, vilka hierarkier man kan ha i budskap, vilka saker som behöver en kampanj och vilka som löser sig automatiskt genom halo effects.

Visst finns det mycket performance-världen kan lära sig av varumärkes-sidan, men det finns också mycket lärande i andra riktningen. Om båda sidor arbetar efter samma principer kring förenkling och kontinuitet, finns det dessutom avsevärda synergier att skapa. Mer om det en annan gång.