(På engelska då den är skriven för econsultancy.com och jag inte orkade översätta till Svenska. Sorry)

Simple, distinctive and categorical statements have a way of becoming truths. That is because they simplify complex patterns, because they slash time for analysis and discussion in processes, and because they make really nice statement slides.

These statements and “rules” range from a very few undisputable ones, over a wide range of statements that are factually based but are subject to conditions and can be questioned depending on scenario, to the outright questionable ones.

A strong brand reduces price elasticity. Can’t argue with that.

The optimal budget distribution between long- and short term advertising is 60/40. Data based insight, yet Binet & Field themselves say that the ratio varies depending on brand maturity, category etc. Also, the distinction of budget posts between advertising and other disciplines can sometimes be blurry, creating some ambiguity. The rule is valid, but in the over-simplified way it is often retold, there can be argued against.

Successful Influencer marketing depends on giving the influencers freedom to create the content they know works for their followers. Seriously believe this can be questioned, at least if you have some faith in the thinking about distinctiveness, singularity and brand asset management.

Innovate or die. We’ve all seen the Kodak slides, but the universal validity of innovation as a necessity is just bonkers.

So while ranging in validity, these statements become absolute truths because they are so simple, and because their simplicity causes them to be repeated in so many trend and strategy decks. After some time, they become so ubiquitous you are considered out of the loop if you don’t mention them – or agree with them for that matter.

Interestingly, the statements you need to agree with are different, depending of in what field you work. They can often be completely contradictory to the ones followed by other, adjacent fields. You work in digital strategy and UX? Of course, the future is cusstumer centric and personalized! Ad agency professional? Naturally most of your efforts need to be emotionally driven and have broad and universal appeal.

One of the laws that have been around long enough to become an accepted truth, and dodged scrutiny and critical examination, is Paretos law.

Vilfredo Pareto, a.k.a. Mr 80/20. Image courtesy of Wikipedia

The Pareto principle (also known as the 80/20 rule,) states that, for many events, roughly 80% of the effects come from 20% of the causes. Management consultant Joseph M. Juran suggested the principle and named it after Italian economist Vilfredo Pareto, who noted the 80/20 connection while at the University of Lausanne in 1896.

In the field of business economics and marketing, Paretos Law has been applied as the understanding that 20% of any brands customers stand for 80% of that brands business. As a consequence, it is concluded that brands are well advised to focus a lot of their energy on these most valuable customers.

A new paper from Byrpn Sharp, Jenni Romanuk and the Ehrenberg Bass institute shows that this relationship is just not true. The reason they wanted to examine Paretos law is exactly that rock solid reputation the 80/20 law has as an indisputable fact. As they quote in their new study;

“I grew up with the 80/20 rule and [before reading How Brands Grow] kind of accepted it for a long time without much thinking. Who could argue with a famous economist?” Jan-Benedict Steenkamp, Professor of Marketing, University of North Carolina

Not only professor Steenkamp has been convinced, a google seach shows over half a million results for 80/20 rule of marketing

But the new Ehrenberg paper shows that the 20% most valuable customers stand for just over half of a brands business, not even close to 80%.

It also shows variation between industries, from the top score for Dog Food at 68% to a low point of 44% for hair conditioner.

Furthermore, the study shows that regardless of brands efforts, consumers move a lot between being heaby buyers, to light buyers or non buyers, and vice versa.

So, what can we learn from the debunking of Paretos Law in marketing? Firstly, that we should be very skeptical of people showing flashy slides with the numbers “80/20” on them without problematising them.

Secondly, and perhaps even more importantly, that we need to do our own background check on even the most accepted laws and principles of our industry. It is important to have a critical mind in an industry where someone could stand to make a lot of money from a principle being accepted. 80/20 rules and “most valuable customer” studies may be more likely to be promoted by the CRM giants, while the TV networks prefer including “broad emotional reach” findings in their trend decks. Without understanding the broader perspective and critically examining how different sets of rules apply and interact, one may easily be misled.

Staying critical, and staying curious. Not a bad rule in itself.

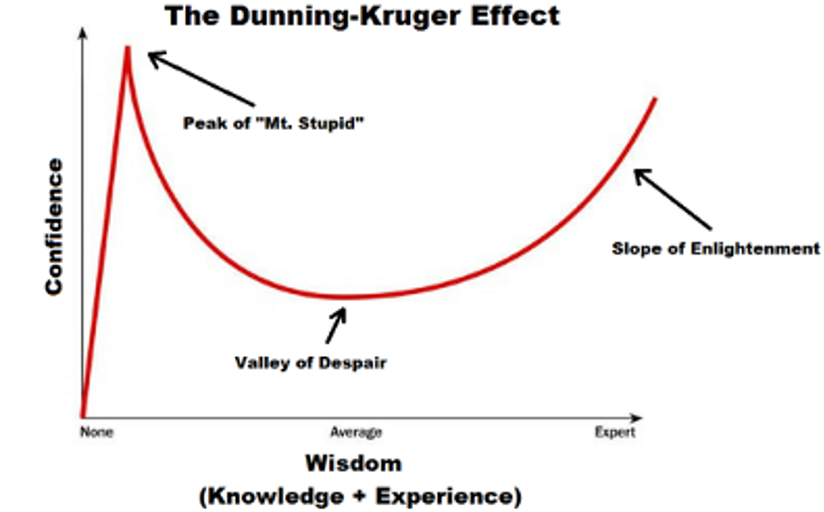

P.S. On the topic of old laws falling, it appears the Dunning Kruger effect is also being questioned.. The Dunning Kruger effect states that the less knowledgeable someone is on a topic, the more headstrong and detailed they are in predictions and statements on that topic. In this, it has been a favourite for criticising over-confident evangelists and futurologists. But alas, it seems everyone’s guesswork is equally crap, regardless of experience in the field.